Originally posted on Conversation Zimbabwe

“All good people agree,And all good people say,

All nice people, like Us, are We

And every one else is They:

But if you cross over the sea,

Instead of over the way,

You may end by (think of it!) looking on We

As only a sort of They!”

~ Rudyard Kipling, Debits and Credits

I open with a quote by a man famous for his literary work on Asia. A non-Asian man himself, Rudyard Kipling was born in what is now India and though he left at the age of 5, his body of work tells us that India and Asia never left him. Perhaps he, like all of us, lived his years appreciating that we are all foreigners here, as well as there.

To me, Kipling’s words resonate. I identify as a Zimbabwean living and working in South Africa. I am Zimbabwean by birth and descent. My father is a Zimbabwean, as was his father’s father, and thus so am I. My South African identify document boldly labels me “Non-SA Citizen.” It tells you that I have lived here long enough, but it reminds you that I am not – at least on paper – a South African, even if part of my ancestry is. I am a kwerekwere.

When your heritage straddles more than one line, crosses rivers and even a sea, you, as with everyone (even without knowing) are a foreigner everywhere you go. It is this knowledge that has made me a passionate opponent of xenophobia, not only in my fatherland, but even more fervently here in South Africa.

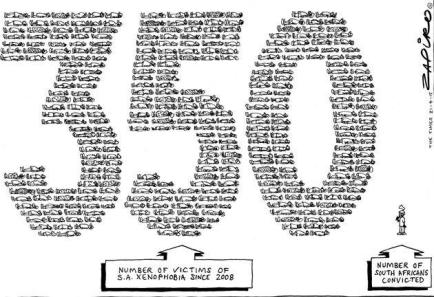

For many in South Africa, “xenophobia” became a buzzword in May 2008 when there were violent rampages targeting foreigners across the country. Meanwhile, others continue to deny the existence of xenophobia in the country. This was not the first time that foreigners were targeted. It was, however, the first that saw widespread attacks. May 2008 was the culmination of decades of simmering tensions and deepseated hatred. The deep historical roots of this social ill cannot be ignored.

On 11 April 2015, as the recent spate of xenophobic violence was flaring up, Business Day editor Songezo Zibi wrote, “I haven’t seen xenophobia in South Africa, just a lot of violent and passive aggressive hate of Africans from outside our borders.” The inherent irony and contradictions within that statement were not immediately apparent to him as he defended his viewpoint from detractors.

Zibi unwittingly highlighted, however, a key characteristic of xenophobia in South Africa; that the primary victims are black Africans. For its uniquely anti-African premise, this xenophobia is often referred to as afrophobia. In 2013, writing on discrimination in South Africa, I noted that racialism and xenophobia can be and are inextricably linked.[iii] The recent outbreak of violence against people from other African countries speaks to this.

Two weeks prior to Zibi’s remarks, Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu, the reigning monarch of the Zulu nation, made  remarks that many have interpreted as xenophobic. In his speech, Zwelithini lamented the influx of “illegal immigrants” who violate and undermine the law. He went further to suggest that foreigners must go back to their countries. For these remarks, some have gone so far as to accuse him of inciting violence against foreigners. One example is Tim Flack from the South African National Defence Union laying a charge of incitement and sedition against the King at the country’s Human Rights Commission. Debate rages as to whether Zwelithini intended to incite violence. The alleged nexus between his words and the resultant violence aside, the reality on the ground is that people are being attacked for being African foreigners. Indeed, to be incited into violence based on someone else’s words, the listeners themselves must have borne these sentiments and perhaps felt vindicated by them.

remarks that many have interpreted as xenophobic. In his speech, Zwelithini lamented the influx of “illegal immigrants” who violate and undermine the law. He went further to suggest that foreigners must go back to their countries. For these remarks, some have gone so far as to accuse him of inciting violence against foreigners. One example is Tim Flack from the South African National Defence Union laying a charge of incitement and sedition against the King at the country’s Human Rights Commission. Debate rages as to whether Zwelithini intended to incite violence. The alleged nexus between his words and the resultant violence aside, the reality on the ground is that people are being attacked for being African foreigners. Indeed, to be incited into violence based on someone else’s words, the listeners themselves must have borne these sentiments and perhaps felt vindicated by them.

remarks that many have interpreted as xenophobic. In his speech, Zwelithini lamented the influx of “illegal immigrants” who violate and undermine the law. He went further to suggest that foreigners must go back to their countries. For these remarks, some have gone so far as to accuse him of inciting violence against foreigners. One example is Tim Flack from the South African National Defence Union laying a charge of incitement and sedition against the King at the country’s Human Rights Commission. Debate rages as to whether Zwelithini intended to incite violence. The alleged nexus between his words and the resultant violence aside, the reality on the ground is that people are being attacked for being African foreigners. Indeed, to be incited into violence based on someone else’s words, the listeners themselves must have borne these sentiments and perhaps felt vindicated by them.

remarks that many have interpreted as xenophobic. In his speech, Zwelithini lamented the influx of “illegal immigrants” who violate and undermine the law. He went further to suggest that foreigners must go back to their countries. For these remarks, some have gone so far as to accuse him of inciting violence against foreigners. One example is Tim Flack from the South African National Defence Union laying a charge of incitement and sedition against the King at the country’s Human Rights Commission. Debate rages as to whether Zwelithini intended to incite violence. The alleged nexus between his words and the resultant violence aside, the reality on the ground is that people are being attacked for being African foreigners. Indeed, to be incited into violence based on someone else’s words, the listeners themselves must have borne these sentiments and perhaps felt vindicated by them.

Dispelling myths and uncovering the irrationality of xenophobia

The reasons for these attacks vary. I will focus on three of the most common and interrelated beliefs.

First, some argue that the country is suffering under the weight of “millions of illegal immigrants.” Estimates vary from 500000 to over 4million. However, most of the estimates are purely anecdotal. Data from the Forced Migration Studies Programme at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg and Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) are most reliable.

The Forced Migration Studies Programme estimated that in 2010, South Africa had a total foreign population of between 1,6 and 2million, of which the number of undocumented migrants was not measured.[iv] In 2013, Stats SA estimated that there are between 500 000 to 1 million undocumented migrants.[v] Relying on the higher end of the scale, if, as Stats SA estimate, there are approximately 1 million undocumented migrants, this would amount to a little under 2% of the population.

The second, and related defence of xenophobia is that these “illegal foreigners” are stealing jobs from locals. This does not compute.

Research by the Migrating for Work Research Consortium (MiWORC) in 2014 found that 82% of the working population was “non-migrants.” MiWORC also found that 14% of the working population was recent “domestic migrants,” i.e. people who had moved between provinces in the past five years. The research lastly found that only 4% of the working population could be classed as “international migrants.” It should be emphasised that that 4% does not just represent migrants from Africa.

Using MiWORC’s and other data, Africa Check, a non-profit organisation that promotes accuracy in public debate, helped dispel the notion that “illegal foreigners” are stealing jobs. Interestingly, research by the Gauteng City-Region Observatory shows that international migrants contribute positively to the economy in various ways, including through employing South Africans.

The third motivator for violence against foreigners is that they are the cause of the crime problem in the country. This, according to the Institute for Security Studies, is a myth.[vi] Stats SA’s National Victims of Crime Survey released in 2014 shows that 95% of the 30000 households surveyed said South Africans committed crime in their area. Also, South Africa’s crime rate, especially violent crime, has long been comparatively very high.

Even if the above three reasons had merit, it would still not justify violence against foreigners. My view is nothing justifies the brutality that has come to be associated with afrophobia in the country.

Importantly, and worth highlighting, not all xenophobia manifests in violence. Attributing xenophobia only to a few – “the angry, ignorant and criminal poor” – is a reckless refusal to take responsibility. This is done, not only by the citizenry, but also by the government in statements that reinforce the belief that xenophobia is “just a crime problem.” Interestingly, while xenophobia is frequently distilled, sanitised and theorised about, all forms of racism are quickly rejected and condemned in South Africa. Racism must not be linked to criminal conduct for it to be seen as racism. The emphasis on the criminal aspect of xenophobia in many ways reduces the seriousness of what is a grave societal problem.

The criminal aspect of xenophobic violence should undoubtedly be addressed. However, addressing the xenophobia as a crime alone is just a symptomatic approach to addressing a deeper societal issue.

Going back to the start

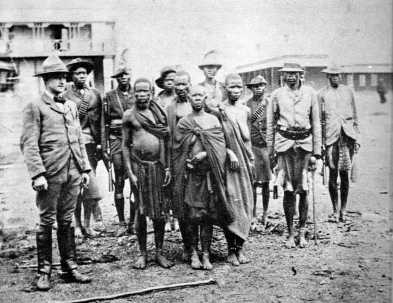

Xenophobia in South Africa, as in all contexts, is a multifaceted social ill with deep hist orical roots. The country’s racially segregated past is, in my mind, a key contributor to the pervasive xenophobia we are witnessing today. The words of a good friend, Luvuyo Mandela, resonate today, and always,

orical roots. The country’s racially segregated past is, in my mind, a key contributor to the pervasive xenophobia we are witnessing today. The words of a good friend, Luvuyo Mandela, resonate today, and always,

orical roots. The country’s racially segregated past is, in my mind, a key contributor to the pervasive xenophobia we are witnessing today. The words of a good friend, Luvuyo Mandela, resonate today, and always,

orical roots. The country’s racially segregated past is, in my mind, a key contributor to the pervasive xenophobia we are witnessing today. The words of a good friend, Luvuyo Mandela, resonate today, and always,“We are all foreigners […]

We come from a history where [we] were systematically & methodically taught to hate anything that was different to [us].”[vii]

In a country where the success of black people is still often viewed with suspicion (with people often saying, “s/he must be related to a political big wig” or “probably an unlawful beneficiary of BEE” or “S/he is a tenderpreneur”) one cannot ignore the patent racialism that informs verbal, emotional, physical and psychological violence against “other” Africans. Indeed, there is a major psychological (and psychosocial) element to the afrophobia and its periodic violent manifestation that must be addressed.

At a peace march in Durban, First Lady Thobeka Madiba-Zuma encouraged people to “tolerate each other.” Commendable as it was that the First Lady was firm in pronouncing herself against xenophobia, preaching tolerance is not the right avenue. “Tolerance,” put simply, means “put up with something you don’t like.” We must be calling on people to do more than tolerate. People must embrace diversity and inclusivity and respect the rights of all.

With a Constitution touted as having one of the most progressive Bills of Rights in the world, on paper South Africa is welcoming. However, South African society must be reminded of the country’s core values. The challenge will be in getting people to recognise the humanity & dignity of “others.” What seems like an obvious and easy ask is, as the ongoing violence shows, a mammoth task for a society in transition.

Part of the title is an ode to NoViolet Bulawayo, an expatriate Zimbabwean author whose book “We need new names,” tells the story of settling abroad and realising that no matter how familiar things may get, you may always remain a foreigner.

A shorter revised version of this piece appears in Foreign Policy magazine

Ottilia Anna Maunganidze

[iii] OA Maunganidze, “No Black and “other” Africans in the Rainbow: A Nation Divided,” Umuntokanje, (2013) http://umuntokanje.co.za/index.php/2013-08-18-09-49-28/2013-08-21-09-10-13/94-no-black-and-other-africans-in-the-rainbow-a-nation-divided

[iv] T Polzer, “Migration Fact Sheet: Population Movements in and to South Africa,”

Forced Migration Studies Programme, (2010)http://www.academia.edu/296416/Migration_Fact_Sheet_1_Population_Movements_in_and_to_South_Africa

Forced Migration Studies Programme, (2010)http://www.academia.edu/296416/Migration_Fact_Sheet_1_Population_Movements_in_and_to_South_Africa

[v] Stats SA relied on information on documented migrants from the Department of Home Affairs

[vi] ISS Press Release: Xenophobia demands decisive and principled leadership, 17 April 2015, http://www.issafrica.org/about-us/press-releases/xenophobia-demands-decisive-and-principled-leadership

[vii] L Mandela, “We are all foreigners somewhere,” Dropthewhy, (2015)http://www.dropthewhy.com/#!We-are-all-Foreigners-Somewhere/c1k5f/553232100cf2251855a5e8bf

in a society that polices what women should wear while leaving the oversize viscose clad men to carry on with their fashion crimes. (In the same week, The Herald asks people if wearing a mini-skirt makes you a prostitute and my eyes roll back to 1986…)

in a society that polices what women should wear while leaving the oversize viscose clad men to carry on with their fashion crimes. (In the same week, The Herald asks people if wearing a mini-skirt makes you a prostitute and my eyes roll back to 1986…)

Like hundreds of other children, he was trained as rebel soldier

Like hundreds of other children, he was trained as rebel soldier