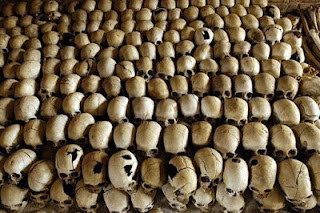

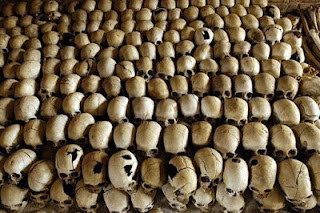

On 6 April 1994, Rwandese president Juvenal Habyarimana and Burundian

president Cyprien Ntaryamira were killed in a plane crash. The two were

travelling from Tanzania to Rwanda following a heads of state summit in

Dar es Salaam. After the crash widespread violence erupted in Rwanda

resulting in the deaths of approximately 800 000 people over the next

100 days. Although it has been alleged that the plane was shot down, to

date the perpetrators have not been identified. The targets of the

Rwandan genocide were predominantly from the Tutsi ethnic group,

although moderate individuals from the Hutu ethnic group who were

believed to be sympathetic to the then opposition Rwandese Patriotic

Front (RPF) were also among the victims.

Eighteen years after the genocide, the quest for justice for the

crimes committed in 1994 continues. An international criminal tribunal

was set up by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to prosecute

those who bore the greatest responsibility for the Rwandan genocide. To

date, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) has dealt

with over 80 cases, securing convictions in 59 of these. The ICTR has

achieved important results as far as accountability for the genocide is

concerned. However, the tribunal has been criticized for taking too

long, being costly to run and prosecuting a small amount of people in

comparison to domestic justice processes in Rwanda. Furthermore, the

ICTR has been criticized for focusing its prosecutions on Hutus.

In addition to those prosecuted by the ICTR, the Rwandan local and

traditional gacaca courts have prosecuted hundreds of thousands of

individuals. The combined efforts of the ICTR, the local courts and the

gacaca have resulted in a unique and comprehensive approach to ensuring

justice for the crimes committed during the 1994 genocide. However,

despite overwhelming success, justice has largely remained one-sided and

slow. In a 2011 report on the gacaca, international human rights

organisation Human Rights Watch criticized the gacaca system and accused

the Rwandan government of political interference in the trials. In

addition, many senior officials believed to be behind the genocide

remain at large and in exile in other countries. These individuals, if

extradited to Rwanda, can only face trial before the High Court and not

the gacaca.Since 1995, the Rwandan government has sent over 40

extradition requests to various countries.

These requests for the extradition of individuals to Rwanda to stand

trial have largely been unsuccessful. However, recent events suggest

that those who remain at large could face trial in Rwanda at last.

On 24 January 2012, Canada deported alleged genocide suspect Leon

Mugesera back to Rwanda. Mugesera appeared before the Rwandan High Court

on 2 February 2012 where he was charged for his involvement in the 1994

genocide. Mugesera, a member of the MRND – the former ruling party in

Rwanda – is accused of inciting and planning the genocide. The charges

against Mugesera are based on a speech he gave at an MRND party meeting

in 1992, in which he called upon people from the majority Hutu ethnic

group to exterminate the minority Tutsis who he likened to cockroaches.

Mugesera’s case is the second high profile case that will be dealt

with by Rwandan domestic courts. His deportation came just days after

the ICTR handed over referral and prosecution materials in the case of

Jean Bosco Uwinkindi to the Rwandan courts. Uwinkindi is charged with

the crimes of genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide and extermination

as a crime against humanity for his involvement in atrocities in Kigal

Rural Prefecture.

Uwinkindi’s transfer is the first handover of a case by the ICTR to

the national courts of Rwanda. The Prosecutor of the ICTR, Hassan

Bubacar Jallow, regards the transfer of the Uwinkindi case as a

watershed moment for both the ICTR and Rwanda. Indeed, the transfer of

the Uwinkindi case to Rwanda is an important step in acknowledging the

ability of the Rwandan criminal justice system to deal with serious

crimes.

In addition to the cases of Mugesera and Uwinkindi, in 2011 the US

returned to Rwanda two genocide fugitives, Jean-Marie Vianney

Mudahinyuka and Marie-Claire Mukeshimana. More recently, the European

Court of Human Rights (ECHR) also approved the extradition of another

genocide suspect, Sylvere Ahorugeze, who is currently resident in

Sweden. The decision of the ECHR, although subject to review, is

important for international criminal justice as it has a broad impact,

particularly in Europe where it is believed hundreds of Rwandan genocide

suspects reside.

The decision of ECHR is the first of a regional human rights court on

the extradition of a genocide suspect to Rwanda. As such the judgment

sets a precedent for Rwanda to seek extradition of other suspects

resident abroad. This decision follows refusals by courts in Belgium,

Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands and the

United Kingdom to allow the extradition of genocide suspects to Rwanda.

Most of these decisions were based on the fact that the courts were not

satisfied that the Rwandan judiciary could guarantee a fair trial to

extradited genocide suspects.

It is no surprise therefore that the Prosecutor General of Rwanda,

Martin Ngoga, has applauded these recent decisions as evidence that the

international community believes in the Rwandan criminal justice system.

He credits the Rwandan government’s legal reforms for these positive

developments. Notably, in 2007 Rwanda abolished the death penalty.

Furthermore, since 2008 Rwanda has engaged in capacity building projects

aimed at enhancing the performance of the judiciary and ensuring

fairness and efficacy of the courts. In addition new courthouses and

detention facilities were constructed.

However, despite these recent decisions and the efforts of the

Rwandan government to reform the criminal justice system, concerns

remain. One of the major concerns relates to whether the Rwandan courts

have the requisite capacity to deal with the potential influx of high

profile cases. In addition, until recently most courts – the ICTR and

those in Europe – did not believe that the Rwandan courts would be able

to provide free and fair trials for genocide suspects. Perceptions are

changing, albeit slowly. The satisfactory performance of the Rwandan

courts will be particularly important for Rwanda’s continued efforts to

ensure accountability given that both the ICTR and the gacaca courts

will end trials in mid-2012. As a result, the latest genocide trials in

Rwanda will be watched closely as they will be the litmus test for any

future extraditions or transfers to Rwanda.

ISS Today article written by Ottilia Anna Maunganidze,

Researcher, Transnational Threats and International Crime Division, ISS

Pretoria

ISS Africa

The

position taken by the African Union towards the ICC creates the

impression that African states are resistant to international criminal

justice. This paper argues that the reality is quite different. The

continent provides many examples of international justice in practice. A

review of selected domestic and regional efforts suggests that a richer

understanding of the Rome Statute’s ‘complementarity’ scheme is

developing – one involving states, regional organisations and civil

society working to close the impunity gap. Such actions are giving

effect to the notion that while the ICC can provide justice through a

few highly publicised trials, for justice to be brought home in any

meaningful way, domestic action is essential.

The

position taken by the African Union towards the ICC creates the

impression that African states are resistant to international criminal

justice. This paper argues that the reality is quite different. The

continent provides many examples of international justice in practice. A

review of selected domestic and regional efforts suggests that a richer

understanding of the Rome Statute’s ‘complementarity’ scheme is

developing – one involving states, regional organisations and civil

society working to close the impunity gap. Such actions are giving

effect to the notion that while the ICC can provide justice through a

few highly publicised trials, for justice to be brought home in any

meaningful way, domestic action is essential.