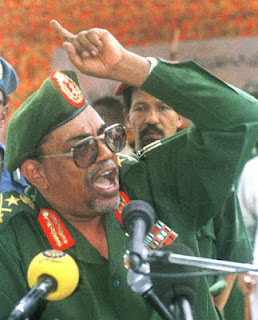

On Friday 8 June 2012, the cabinet of Malawi resolved not to host the next African Union (AU) Summit because the AU insisted that all Heads of State - including Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir - be invited to attend.

Al-Bashir is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) on charges of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide allegedly committed in Darfur. The decision by Malawi's President Joyce Banda not to allow al-Bashir into her country because of Malawi's international obligations has led to widespread reaction throughout Africa.

Malawi's Vice-President Khumbo Kachali made the announcement on Friday 8 June that Malawi would not submit to pressure from the AU to invite Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir to the upcoming AU summit. Kachali stated that, 'much as Malawi has obligations to the AU, it also has other obligations (and) the Cabinet has decided not to host the summit'.

It has been widely reported that President Joyce Banda's decision not to invite al-Bashir and the pursuant decision by the Malawi cabinet are informed by the country's efforts to regain international favour. This kind of speculation could have political implications for Malawi, especially for its relationship with the AU going forward. The political issues surrounding this decision have unfortunately overshadowed the legal dimension of the issue. Of importance in this regard are the United Nations (UN) Charter, the Constitutive Act of the African Union, and the Rome Statute of the ICC. All these instruments, which are binding on Malawi, have specific provisions aimed at promoting global peace and the rule of law, and ending impunity.

First, the UN Charter enunciates as one of its principles the need to maintain international peace and security. Malawi, as a member state of the UN, is bound to its decisions. Under Article 103, the UN Charter provides that obligations under the Charter prevail over any other obligations if there is a conflict. It should be noted that the situation in Darfur was referred to the ICC pursuant to UN Security Council Resolution 1593 in 2005. The UN Security Council invoked its powers under Chapter VII of the UN Charter and provisions in the ICC Statute to oblige the Government of Sudan and 'all other parties to the conflict in Darfur' to cooperate with the ICC (which includes the arrest and surrender of suspects to the court).

Second, one of the primary objectives of the AU is to achieve peace and security in Africa. Specifically, the Constitutive Act of the AU provides a legal framework for the continental organ to fight impunity. Articles 4(h) and (o) of the Constitutive Act authorise the AU to intervene in member states to stop war crimes, genocide, crimes against humanity and ultimately to prevent impunity. However, it should be noted that this intervention is often political.

Last, but certainly not least, is the fact that Malawi's decision is in line with the country's responsibilities under the Rome Statute of the ICC. As an ICC member state, Malawi is obliged to cooperate fully with the ICC in its investigation and prosecution of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, and where requested to arrest al-Bashir (and any other suspects wanted by the ICC) if he visits the country and surrender him to the court. Malawi's decision to arrest and surrender al-Bashir to the ICC should he enter its territory is not unique. Indeed, Malawi's stance is not the first, nor shall it - hopefully - be the last in Africa.

In April 2009, al-Bashir - although invited - decided not to travel to South Africa to attend President Jacob Zuma's inauguration. This decision came after South African authorities and civil society took steps to exercise the country's domestic and international criminal law obligations with regard to al-Bashir. Following similar actions by governments and African civil society organisations, other states have found diplomatic solutions to either avoid al-Bashir's visits or move the venue of important meetings to the territory of non-states parties.

Notably, al-Bashir cancelled trips to Uganda in 2009 and 2010 over fears that he would be arrested, and also did not attend Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni's inauguration in May 2011. Furthermore,

al-Bashir did not attend the ceremony of the 50th anniversary of the independence of the Central African Republic (CAR) in December 2010. Both Uganda and CAR are states parties to the ICC Statute and referred the situations in their respective countries for investigation and prosecution at the ICC. Later that December, al-Bashir cancelled his trip to Zambia (also a state party to the ICC Statute) to attend the International Conference for the Great Lakes Region following international protest. Instead, Sudanese foreign minister Ali Karti and minerals minister Abdel-Baki Al-Gailani attended the summit. Other African countries like Botswana have made it clear that al-Bashir is not welcome.

Nevertheless, since the arrest warrant was issued in 2009, al-Bashir has been able to travel to several countries that are obliged to arrest and surrender him to the ICC, including ICC member states Chad, Djibouti, Kenya, and Malawi in 2010 and 2011. It is worth noting that following his first visit to Kenya in August 2010, civil society action resulted in the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) moving its October 2010 special summit on Sudan from Nairobi to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia to

avert a potential diplomatic quandary over al-Bashir's attendance. Further, civil society was in 2011 able to secure a warrant for his arrest from a Kenyan High Court, thereby preventing subsequent visits.

It is clear that African states are divided on the al-Bashir issue. This is despite AU decisions in 2009, 2010, 2011 and January 2012 in which the AU called on all its member states not to cooperate with the ICC in respect of al-Bashir's arrest warrants. The AU argues that, as a head of state, al-Bashir enjoys immunity and should therefore not be prosecuted while in office. The AU also contends that arresting al-Bashir would not be in the interests of peace and would undermine its ongoing efforts to negotiate a peaceful settlement between Sudan and South Sudan.

Despite the AU's decisions on al-Bashir, the facts of the Sudanese president's trips noted above show that some African states have chosen to abide by their domestic and international legal obligations rather than the AU position. These countries, some of which have vowed to arrest al-Bashir, are acting consistently with the rule of law requirements of international criminal justice. However, others abide by the AU decisions even though this means flouting the rules of the ICC.

Interestingly, some countries like Malawi have shown a shift in opinion. In October 2011, before the death of Malawi's former President Bingu wa Mutharika, al-Bashir was able to travel to that country for a regional economic summit. However, with the change in government, the stance in Malawi on international criminal justice has also significantly shifted. But is it enough?

The fact that al-Bashir has not yet been arrested and surrendered to the ICC is evidence that for international criminal justice to succeed, countries, especially ICC states parties, must do more than take principled positions. They must be ready and able to apprehend people indicted by the ICC. It is the lack of full commitment to cooperating with the ICC that led the court's outgoing chief prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo to request the UN Security Council to consider calling on all UN member states and regional organisations to carry out the arrest warrants for al-Bashir and other indicted Sudanese officials. It remains to be seen whether the UN Security Council will oblige and what implications such a move will have.

Malawi should be applauded for its principled and legally correct position on al-Bashir. At the same time, the AU's determination to bring together all heads of state, especially those directly involved in continental conflicts, is understandable and in line with its chief mandate to promote peace and security. Thus moving the summit to a non-state party to the ICC is arguably the right result under the circumstances. However, it is unfortunate that once again peace and justice have been set up against each other in such a polarising manner. It will serve the interests of peace, justice and the rule of law if African leaders are proactive in finding solutions that are both diplomatic and not in breach of international law.

Ottilia Anna Maunganidze is a researcher in the Transnational Threats and International Crime Division of the ISS www.issafrica.org