13 November 2013

On

5 November 2013, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) began

handling the request to defer the International Criminal Court’s (ICC)

cases in the Kenyan situation. The request, which was submitted on 1

November for consideration by non-permanent members Rwanda, Togo and

Morocco under instruction from the African Union (AU), relates

specifically to the cases against Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta and

his Deputy, William Ruto.

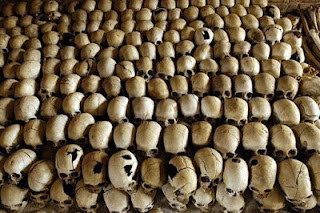

Kenyatta and Ruto (together with Kenyan journalist Joshua Sang) face charges related to the violence that erupted after Kenya’s December 2007 elections, in which over 1 100 people died. Ruto and Sang’s trial began in September 2013, while Kenyatta’s trial is due to start on 5 February 2014 after a third postponement.

In October this year, the AU held an extraordinary summit at which the relationship between the ICC and Africa was discussed. Central to the discussions was the fact that all cases currently before the ICC are from African countries, including the indictment of two sitting heads of state. In its 12 October 2013 decision, the AU called for the Kenyan cases to be deferred and asked that the UNSC provide feedback on the deferral request by 12 November 2013, the date on which Kenyatta’s trial was scheduled to start.

Even if heard, despite support from Russia and China, the likelihood of the deferral being granted is slim, given that the United States, United Kingdom and France, who all hold the power to veto resolutions, insist that the ICC’s postponement of Kenyatta’s trial to February next year was sufficient. The views of the five permanent members of the UNSC notwithstanding, it is essential to assess the merits of the deferral request itself.

Article 16 of the ICC’s Rome Statute, in terms of which deferral requests can be made, statesthat ‘No investigation or prosecution may be commenced or proceeded with … for a period of 12 months after the Security Council, in a resolution adopted under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations, has requested the court to that effect ….’ Chapter VII of the UN Charter empowers the UNSC to take measures to ‘maintain or restore international peace and security’ if it has determined ‘the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of peace or act of aggression’.

First, it is clear that Article 16 is intended for use in exceptional circumstances. Indeed, the UNSC has not, to date, deferred any ICC investigation or prosecution. The question now is whether continuing the court processes would undermine international peace and security. The AU’s request stresses that Kenya’s leaders need to focus on the ongoing fight against terrorism, especially following the attack on Westgate mall in September. They contend that having the president and deputy president of the country on trial jeopardises this.

This is not a widely supported view. Notably, Kenyan human rights organisations, in a letter to the president of the UNSC, stated that conflating the two issues would undermine accountability. The organisations emphasised that deferral on this basis would actually further embed impunity, which lends itself to susceptibility to terrorism.It cannot be denied that terrorism is a serious threat in Kenya and the Horn of Africa region. However, the UNSC has to decide whether this suffices as a basis upon which to allege that continuing the trials will compromise international peace and security. Indeed, counter-terrorism and international criminal justice are bedfellows in that they both seek to address serious crimes that have an adverse effect on global peace and security, and where the two intersect a balance must be struck. One should not be preferred over the other.

Second, the AU claims that by virtue of their positions as president and deputy president of Kenya, the two accused should not, for the duration of their terms, be prosecuted. The AU argues that doing so would undermine Kenyatta and Ruto’s official duties. If the deferral were granted on this basis, it would contradict Article 27 of the Rome Statute (which denies immunity for heads of state and other senior government officials). Significantly, it would mean the deferral would have to be renewed every 12 months for the duration of the Kenyan presidential term of five years. Presupposing that Kenyatta runs for a second term and wins, the deferral would have to be extended for a further five years.

This, as noted by Fergal Gaynor, the legal representative of victims in the case against Kenyatta, would further unduly delay any justice for the victims – assuming that Kenyatta is indeed found guilty. Similar sentiments have been voiced by civil society, including the Kenyan Human Rights Commission and the International Center for Policy and Conflict. Importantly, this argument of the AU contradicts Article 2(6) and Article 143(4) of the Kenyan constitution. Article 143(4) specifically prohibits the president’s immunity from criminal prosecution for ‘crime[s] for which the President may be prosecuted under any treaty to which Kenya is party and which prohibits such immunity’. The deputy president enjoys no immunity from prosecution under the Kenyan constitution.

Third, the AU contends that the criminal justice reforms undertaken in Kenya sufficiently allow for national prosecutions of those responsible for the post-election violence. While, on the face of it, this is in line with the ICC’s role as a court of last resort and is thus commendable, it is not a basis for deferral. Indeed, this was the primary basis of Kenya’s own deferral request made directly to the ICC in 2011, which the Court rejected. Supposing the criminal justice reforms were considered in making the decision, the argument ignores the fact that despite these reforms, there have been few prosecutions and convictions for serious crimes committed during the post-election violence. More importantly, if the ICC is to reconsider its jurisdiction in this situation, the Kenyans who stand accused by the Court are unlikely to be prosecuted domestically.

Further, in early September, Kenya’s parliament passed motions aimed at withdrawing Kenya from the Rome Statute and repealing the country’s International Crimes Act, which, among other things, provides a basis for the prosecution of ICC crimes in Kenya. This move would mean that not only are the president and his deputy free from prosecution for international crimes, but so are all Kenyans. This goes against the spirit and purpose of international criminal justice and is a blatant denial of recourse to justice for the victims of international crimes.

These are the key matters that the UNSC must grapple with in deciding whether or not to defer the ICC cases against Kenyatta and Ruto. At the end of the day, this will be put to a vote. A resolution on deferral can only be passed if at least nine countries are in favour and none of the five permanent members use their veto. That is unlikely, but not impossible.

Ottilia Anna Maunganidze, Researcher, Transnational Threats and International Crime Division, ISS Pretoria